That much for the short history of whaling…

Whaling, outlawed since 1986 when the IWC adopted a moratorium on commercial whaling, still clings on by the skin of its teeth and has not been completely abandoned despite the ban. What is the motivation behind it—and is it really necessary to keep it alive? Let’s dive in.

Early Whaling: Survival and Trade

The first recorded instances of whaling date back to at least 3000 BC. Coastal communities in Japan, Norway, and Arctic regions hunted small whales using simple tools such as harpoons and boats. Whales provided essential resources, including meat for food, bones for tools and construction, and blubber for oil used in lamps and heating. Over time, whaling became a profitable trade, expanding beyond local subsistence hunting.

The Rise of Commercial Whaling

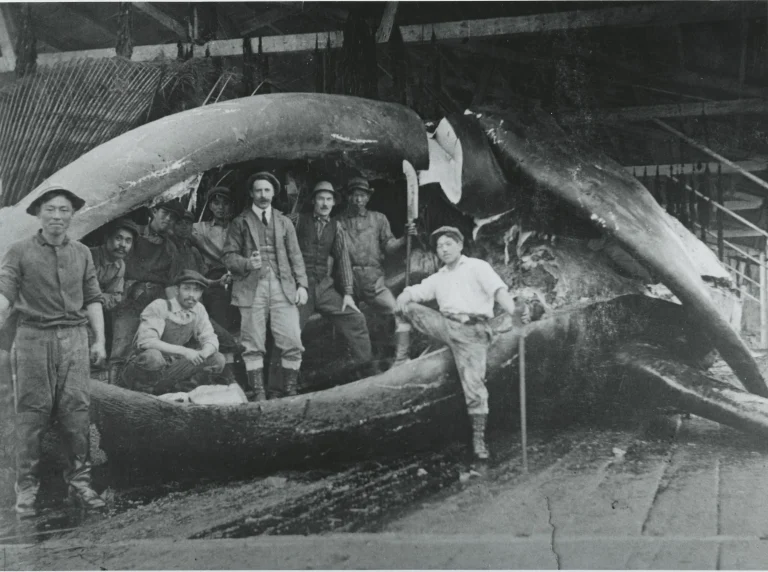

By the 16th century, European nations such as Spain, the Netherlands, and England began large-scale whaling operations. The Basques were among the first to develop sophisticated whaling techniques, targeting species like the North Atlantic right whale.

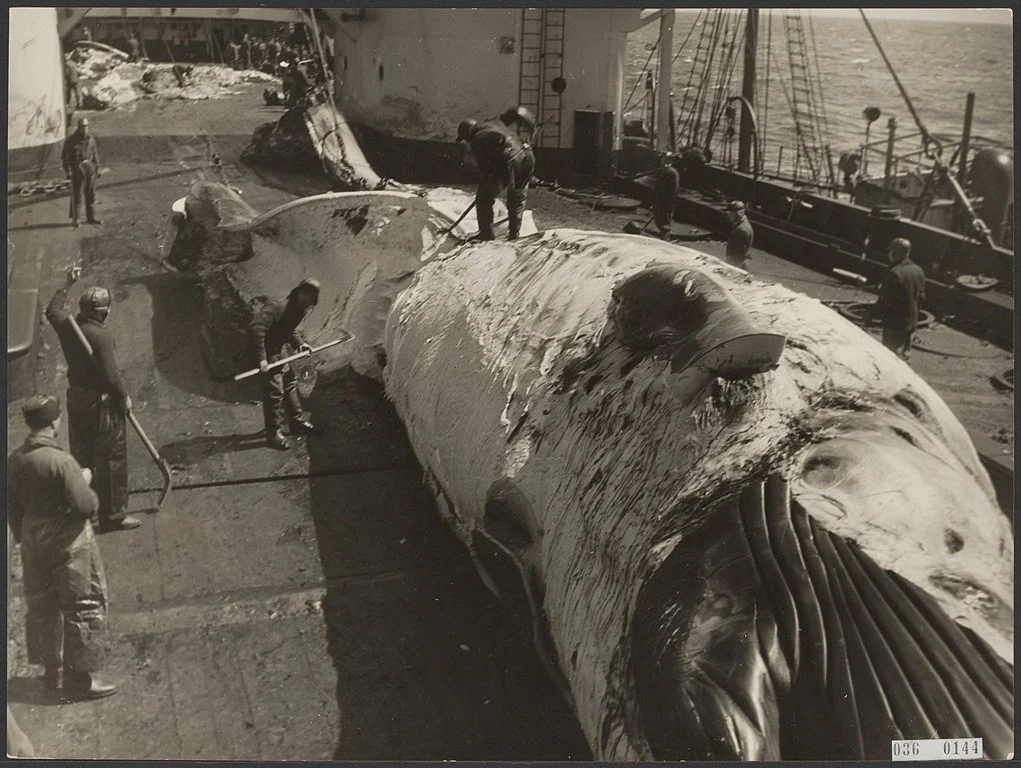

Image credit: Unknown, Nationaal Archief

Industrial Whaling and the Decline of Whale Populations

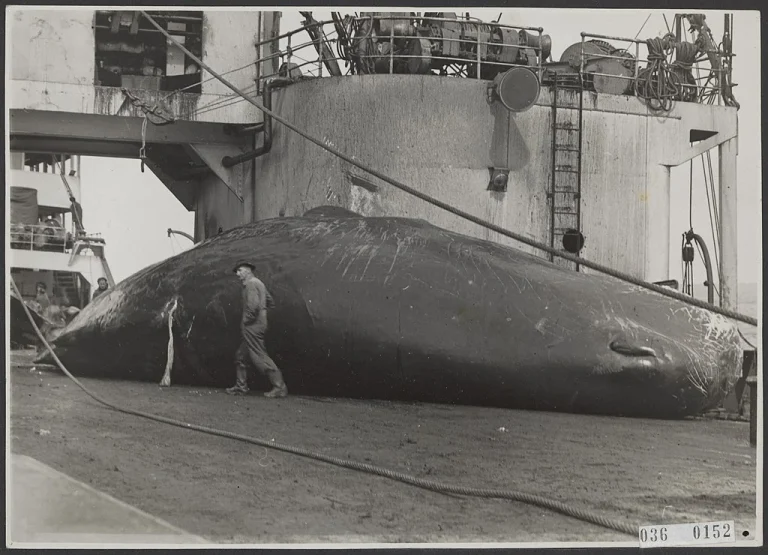

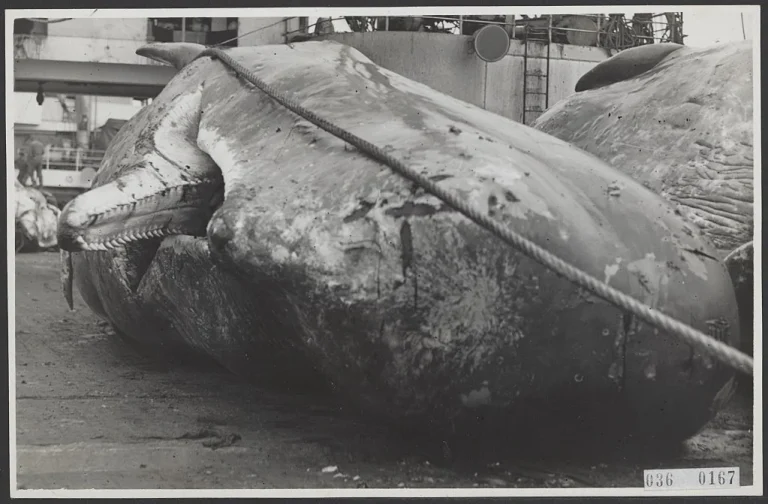

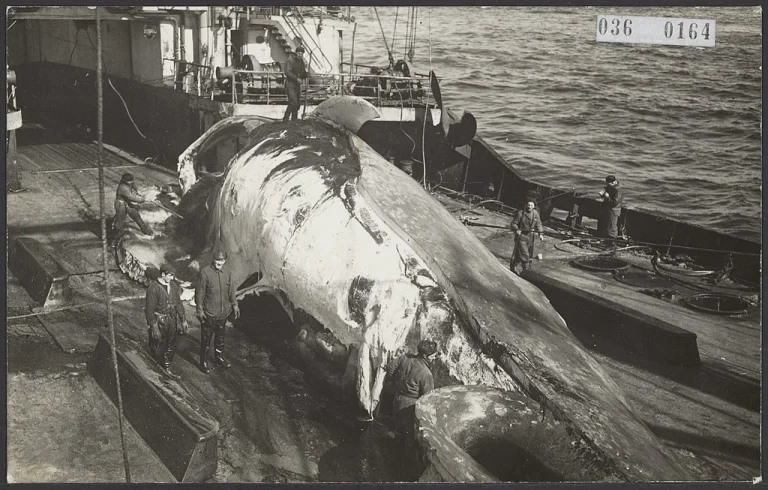

The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the introduction of steam-powered ships and explosive harpoons, drastically increasing hunting efficiency. This period brought a devastating decline in whale populations, with thousands of whales slaughtered annually.

A major base for the UK whaling industry during the early 20th century was South Georgia Island, located near Antarctica. The island housed processing stations where thousands of whales were brought for oil extraction and other products. The UK was not the only nation to upscale whaling to large-scale industrial hunts. Other nations such as Norway, the US, and Japan followed the same model, adapting to the increasing demand for whale products. Large motherships were introduced to process whales at sea, increasing the industry’s efficiency even further. All together, the results were devastating.

Harpoon mounted on a whalng boat, Alaska 1915. Image credit: John Nathan Cobb

Industrial Whaling timeline

Conservation Efforts and Modern Whaling

With the implementation of the 1986 whaling ban, many whale species began to recover. Their comeback stands as a powerful example of a successful conservation story. However, some nations continue to hunt whales under specific exemptions:

Japan resumed commercial whaling in 2019 after withdrawing from the IWC.

Norway openly defies the ban, hunting hundreds of minke whales annually.

Iceland also engages in commercial whaling, though on a smaller scale; currently, the whaling season has been paused.

Indigenous Whaling: Some communities in Alaska, Canada, and Greenland are allowed to hunt limited numbers of whales for cultural and subsistence purposes.

Moreover, modern threats like industrial krill fishing in Antarctic waters now endanger the whales’ food source. Many species — including whales and penguins — depend on krill, and depleting this resource could trigger a collapse of Antarctica’s fragile ecosystem.

Antarctic krill (Euphausia_superba) by Uwe Kils -Wikimedia Commons

Looking Back — and Ahead

In the past, whale hunting was about providing vital resources such as food, bones, and oil. Today, none of the whale hunting nations suffer from food shortages—let alone depend on whale products. A 21st-century society can fully function without whaling, rendering this cruel practice obsolete.

Hardly anyone believes that over 1,000 whales need to be killed annually for “scientific” purposes. In reality, much of the whale meat ends up in pet food, as consumer demand continues to decline—even in countries that still practice whaling despite the international ban.

When we assess the risk/benefit ratio of ending whaling once and for all, the answer is clear. Whales are more valuable alive—not just commercially, through tourism—but ecologically. Their role in maintaining the health of our oceans is irreplaceable. These highly intelligent and social creatures contribute to ecosystem stability in ways we are only beginning to understand.

Image credit: Zac Bowling on Unsplash

Taking the Final Step

Whales have been hunted for thousands of years—initially for survival, later for profit. While commercial whale hunting has largely been banned, a few nations persist. Conservation efforts have proven that whale populations can recover if given time.

Let’s make it easier for whales. Let’s eliminate all the remaining factors that hinder their recovery.

Whales belong to the ocean, and they are our crucial allies in these challenging times—and those to come.

Support whale conservation

Post credits

Image credits: Nationaal Archief on Wikimedia Commons (copyright author unknown)